Hilbert's Grand Hotel and The Guessing Game: Infinity in Disguise

Infinities. They are, well, infinite. Like very big, infinitely big. Remember back in primary school when you would compete with your friend about who can say the greatest number? Your friend would start off as 1, then you 2, him 3, 4, etc. But your friend, who didn’t want to lose (don’t we all), says “Infinity!!” What do you do? You say “Infinity plus 1!” But at that point the contest wouldn’t make sense anymore. What is infinity plus one? Isn’t infinity already the greatest number? But Mathematicians today aren’t just contented with that one infinity, at least one wasn’t in the past. Back in the 1800s, while other mathematicians were contented with infinity being big and just that, one Mathematician showed that some infinities are larger or smaller than others. Georg Cantor introduced cardinals, or sizes, of infinity.

(Just a note: Your mind is going to get really stretched while you read this. I have condensed it as much as possible for you to understand while giving you interesting facts along the way. It is long but it will be interesting.)

The Concept of Infinity

Before we start, I need to get something straight. Personally, I find it very annoying whenever I hear people say things like “Zero divided by zero equals infinity” or “If you add all the numbers together you get infinity”. Infinity isn’t a number, it’s a size. How big is the universe? Infinitely big. How small is an electron? Infinitely small. You don’t say ‘the sum equals infinity’ or ‘you add these to get infinity’, you say it tends to or approaches infinity. This is because infinity is a concept way beyond our brain, yet we learn it to understand the vastness of the things around us. You can’t quantify infinity. Infinity doesn’t have an end nor a start to it; it just isn’t a value. For example, look at the sum of 1+2+3+4+…. At what point when you add the numbers do you say it is the start of infinity? If you keep adding the numbers you know it equals some value, and you also know that it’ll become very big. But at what point would you stop and say “Ok, this is too big. Time to call it a day and just say its infinite.”? This is what its meant by there is no start, no end. Our number line is also the same. No matter what number you think the line starts or ends at, you can always add or minus 1 to the number and you’ll get the numbers before it and after it, meaning the line will keep on going with no bound.

Satisfied with that? Great. Now we can look at the different types and cardinals (sizes) of infinity. And there are two ways of looking at them both: through a normal number guessing game, and a trip to David Hilbert’s Grand Hotel.

Guess a Number, any Number

There are two types of infinity: Countable Infinity and Uncountable Infinity. (Yes, infinities can be either counted or uncounted.)

First, countable infinity. To illustrate this, guess a positive integer, aka whole number. It can be as big as you want, like 2,304,596, or as small as you want, like 1. Done? Whatever number you’ve picked, I can always reach that number in a finite number of steps. Say your number was 24. I can start guessing from 1, then 2,3,4,… until I’ve reached your number. This is countable infinity. No matter how big your number is, I will always be able to guess your number in a limited number of steps through this method (with a limited number of responses from you saying no as well as I count up the number line).

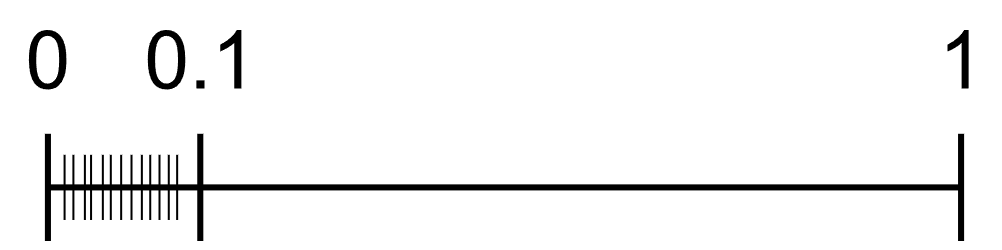

And then there’s uncountable infinity. Instead of limiting you to a positive integer, you can now guess a positive real number. Pi, square root 2, 24, any positive number. You got a number? Good. Now, because I have given you the choice of a real number, and not just integers, if I used the same method as before to guess your number, I will not even be able to start. Because the real numbers are so big, I will always miss numbers when I start. I could start guessing at 0.1, but then that means I would have skipped numbers 0.01 to 0.09. If I started at 0.01, I would have skipped 0.001 and 0.009 and so on. No matter what number I start from, there will always be a number before it that I have skipped, and that number could have been yours. This is uncountable infinity. No matter what your number is, I will not even be able to start guessing what it is, because I will always miss numbers before it.

As you can tell from this, the number of real numbers are apparently much more than the number of positive integers. And you would be right. The positive integers are just 1,2,3,4…. Very consistent. Meanwhile the real numbers can’t even escape the boundaries of 1! You could start counting from 0.0000…00001, as many 0s as you want, but there will always be a number below it you missed.

The infinity of the positive integers is known as, and was shown to be, the smallest infinity. It has a cardinality of aleph-null, the smallest of the cardinals. The infinity of the real numbers, however, isn’t aleph-one, the one after aleph-null. Mathematicians have not been able to show that the real numbers have a cardinality of aleph-one. They know that it is larger than aleph-null, but do not know if it’s aleph-one. (Some believe it is aleph-one, but have not been able to prove it as well. This is known as the Continuum Hypothesis.)

Well, by now I’m sure your brain has been stretched a bit, if not all of it. But before we embark on our trip to the hotel, let me show you that what our intuition tells us in life may not always be the most logical one, but it may be the safest one to prevent our brain from being stretched to its limits.

They’re All the Same Size!

As seen in the previous part, the set of positive integers has the smallest size of infinity, aleph-null. But many other number sets have the same size as it. But how do we show this? Well, suppose you have a set of numbers {1,2,3,4,5,6} that has a size 6. We can show that this set {2,4,6,8,10,12} has the same size of 6 as well. By pairing only one number from the first set with only one other in the second set, 1 with 2, 2 with 4, 3 with 6 etc., we can see that no numbers will be left over and that each number from each set has a partner. This is what’s called a one-to-one correspondence. If one element from a set can be paired with only one other element in another set, both set are said to have the same size, same cardinality.

Just with the example above, I’ve shown you something that might go against your intuition already: The set of positive even numbers has the same cardinality as the set of positive integers. Yes, I used small finite sets in the example, but if I were to keep on adding positive integers and even numbers to the sets, they will still keep forming a one-to-one correspondence with each other. For the positive integer n, it can be paired with the positive even number 2n. You might be scratching your head now thinking, “But isn’t the set of positive integers half full of even numbers? Shouldn’t the set of even numbers be half as big?” And it is not wrong for you to think that, it is logical. But for infinity, it doesn’t work that way. As long as you can pair the numbers from both sets one-to-one, they are the same size. But, as you can see from the pairing of n and 2n, the even numbers grow twice as fast as the positive integers. So while their sizes are the same, the evens would reach the ‘finish line’ first if there was one.

Similarly, the odd numbers, being the other half of the positive integers, has the same cardinality as the even and positive integers. For the positive integer n, it can be paired with the positive odd number 2n-1.

But here’s where your mind is going to get stretched again: The set of positive rational numbers has the cardinality aleph-null as well. Rational numbers are numbers that can be represented as ratios, which are fractions. ½, ⅓, ⅛ are examples of rational numbers. But I’m sure your intuition is telling you, “but won’t there be much more fractions than integers since you can go 1/1, ½, ⅓, …, then 2/2, ⅔, 2/4, … and much more?” Well, the easy way of saying it is that, most fractions like 1/1 and 2/2 are the same thing, since they are just different ways of representing 1, and fractions like ⅔ and 4/6 are also the same, since 4/6 can be simplified down to ⅔. If you were to remove all the repeated fractions, they would be the same size. But you can’t really visualise that, right? So let’s look at it another way.

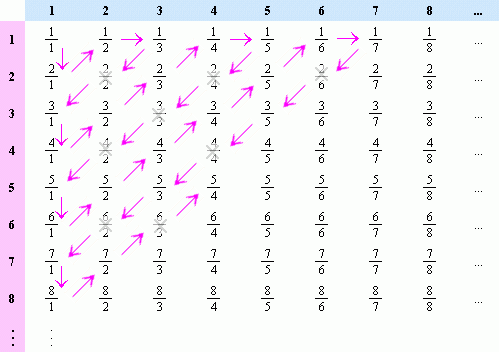

We know from the previous section that the positive integers, and henceforth the even and odd positive integers, are countable. That is, it would take a finite amount of steps to reach a goal. So let’s show that the rational numbers are also countable. To do this, let’s create a table, where the rows and columns are the set of positive integers. So the fraction 1/1 would be in the 1st column of the 1st row, ½ in the 2nd column of the 1st row , ⅓ in the 3rd column of the 1st row and so on.

From this table we can see that the numerators correspond to the row and the denominators correspond to the column of positive integers. So, we can see that, for any positive rational number we want, it will only take a finite amount of moves to reach it. For a rational number n/m, we just have to move n steps down and m steps across to reach it, aka the nth row and the mth column. For example, if we want the fraction 407/328, we just have to go 407 steps down the table and 328 steps across to reach the 407th row and the 328th column. Since every number takes a finite amount of steps to reach, the positive rational numbers are countable and hence the same size as the positive integers.

You may be wondering why throughout this section I’ve only talked about the positive numbers, but don’t worry, the negatives will come later on. Now with your brain stretched and your mind filled with infinities, we can now take the trip to Hilbert’s Grand Hotel. But beware, the hotel holds a nasty surprise and has a few tricks up its sleeve.

Vacancy 1, Filled Up 0

Hilbert’s Grand Hotel is just like any other hotel. It has rooms to sleep in, you can book in and out, it has a restaurant and souvenir shop and much more. But what sets Hilbert’s hotel apart from other hotels is the vacancy in it. Hilbert’s hotel is never full (most of the time anyway). It has infinitely many rooms being able to accommodate every tourist that goes there. All its rooms are labelled as Room 1, Room 2, Room 3 and so on. Want Room 1,246,206,477? They got it. Want Room 69,420,618? Enjoy your stay. As such, it is a common hotel to stay at by the Infinity Tourist Agency, where they have tourist buses infinitely filled with tourists waiting to stay at Hilbert’s massive hotel.

The first bus to arrive is the Positive Integers Group. Each tourist has been given a positive integer; the 1st tourist 1, 2nd tourist 2 and so on. With so many tourists, will there be a problem with space? Of course not. The staff are experienced with this sort of situation. They assign the tourist with number 1 to Room 1, the tourist with number 2 to room 2 and so on. Tourist with number n to room n. Piece of cake.

But now a taxi appears. Turns out there was a tourist who missed the positive integers bus! But we have filled the whole hotel, right? But remember, there are an infinite number of rooms, and the staff are fully prepared. They ask tourist 1 to move from Room 1 to Room 2, tourist 2 from Room 2 to Room 3 etc. So tourist n will move from Room n to Room n+1. Now Room 1 is vacant for the late tourist to stay in! Likewise, if the tourist in Room 1 has to leave, we can move the tourist in Room 2 to Room 1, from Room 3 to Room 2 and so on. The tourist in Room n will move to Room n-1. All the tourists will be taken care of. We have shown, in a sense, infinity plus one or minus one is still infinity (in this case I’m using infinity loosely but remember, it isn’t a number).

Similarly, when the Positive Even Group and Positive Odd Group show up to stay, it will be taken care of. The positive even number tourists stay in the even rooms, and the positive odd number tourists in the odd rooms. Infinity plus infinity is still infinity.

Now a different busload of tourists arrives. It’s the positive integers tourists again! But now, they have brought along their twins; their negative twins. And the coach wants a room like them too, who kindly labelled himself as number 0. This is the Integers Group! Like Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, the positive are sure they can find a place to stay, but the negatives doubt that the hotel can accommodate them all. But the staff at the hotel are about to prove them wrong.

First the staff gather the positive tourists and label them 1, 2, 3 and so on accordingly. Then, instead of placing them in the rooms according to their number, they place them into the odd number rooms. So tourist 1 takes Room 1, tourist 2 in Room 3, tourist 3 in Room 5 and so on. Similarly, the staff then gather the negative tourists and label them -1, -2, -3, etc. But now, they place them in the even number rooms. Tourist -1 in Room 2, Tourist -2 in Room 4, tourist -3 in Room 6 and so on. As such, the tourists and their twin are in alternating rooms: 1, -1, 2, -2, 3, -3, …. And as we’ve seen with the positive odd and even groups, they fit perfectly in. So the hotel triumphs again in sorting the tourists in! But what about the coach? Just like what the hotel did with the late tourist, all the integers just have to move one room up and the coach has a place to stay in. Another point for the hotel!

Now for the 3rd trip, comes the Positive Rational Number Group. As we’ve seen from the section before, the positive rational numbers can be placed in a square with columns and rows of the positive integers. And while the hotel has infinite rooms, it has infinite floors as well. So the tourist with the number ½ will stay in Room 2 of the first floor, ⅔ in Room 3 of the second floor, 215/297 in Room 297 of the 215th floor and so on. The hotel wins again!

But now comes the manager of Hilbert’s Hotel: Georg Cantor himself! While the hotel was of Hilbert’s design, Cantor himself laid the infinite foundations of it. While impressed at his staff for being able to fit the positive rationals in, he notices a problem with it. While the tourist 1/1 will be in Room 1 of the first floor and 2/2 in Room 2 of the second floor, both are actually the same tourist. So Room 2 of the second floor will be empty. Likewise, some of the rational tourists are actually the same ones, just in different clothing. So there are many rooms on each floor that are empty. But Cantor himself has a plan to fit all of them onto just one floor of infinite rooms. But how will he do that? We’ll see how he does it in the next section. But Hilbert’s hotel has done it again!

But now comes a bit of trouble. The bus of Real Numbers has arrived. And not even the full lot; just the numbers from 0 to 1, where tourist 0 is in the front seat and tourist 1 all the way in the back. The staff are flustered by its large size, even larger than the others combined (which is still the same infinity, since adding infinities is still infinity). But they are not going to give up. As they keep on sorting numbered tourists into rooms and onto different floors, Cantor the manager comes out and tells them to stop. He knows that no matter how many tourists they try to fit in, they will always miss one tourist in the sorting. For the Real Numbers, the hotel just can’t fit them all in. Hilbert’s Hotel, quite literally, faced the real deal.

Diagonal and A Special Sequence of Everything Rational

So how did Cantor managed to show that the rationals could fit on just one floor of infinite rooms, and why no matter how long or hard the staff try to fit all the tourists in the rooms, there will always be one tourist unattended for?

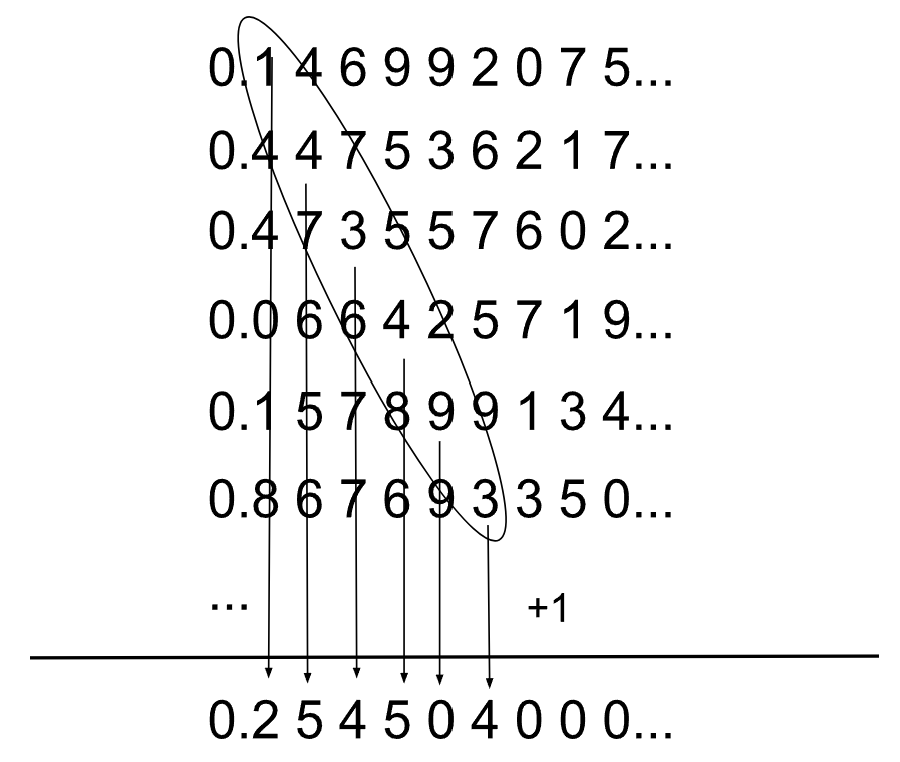

Let’s answer the second question first, because the first will require a bit of thinking. First, randomly write down as many numbers between 0 and 1, as many decimal places as you want. 0.11465…, 0.31415926535…, 0.24681012…, the choice is yours. Now, what Cantor managed to show is that if you put the numbers in a list, he can produce a number that was not in the list. But how?

Well, after you put your numbers in a list, you could potentially sort those ‘tourists’ into the rooms of the hotel. Your first random number in Room 1, the second random number in Room 2 and so on. Now, after you have sorted your numbers out, the magic happens. Take the first decimal place digit of your first number and add 1 to it and write this down somewhere. Do the same for the 2nd decimal place digit, the 3rd and so forth (If the digit is 9 it will become a 0). What you would have is a number where its nth decimal place digit is 1 more than the nth decimal place digit of your nth random number. You have created a number that was not on the list. Since it wasn’t on the list, it was never assigned a room to it.

This was what Cantor called Diagonalisation. No matter how many numbers you produce and how long they are, there will always be one number that can be produced that isn’t on the list.

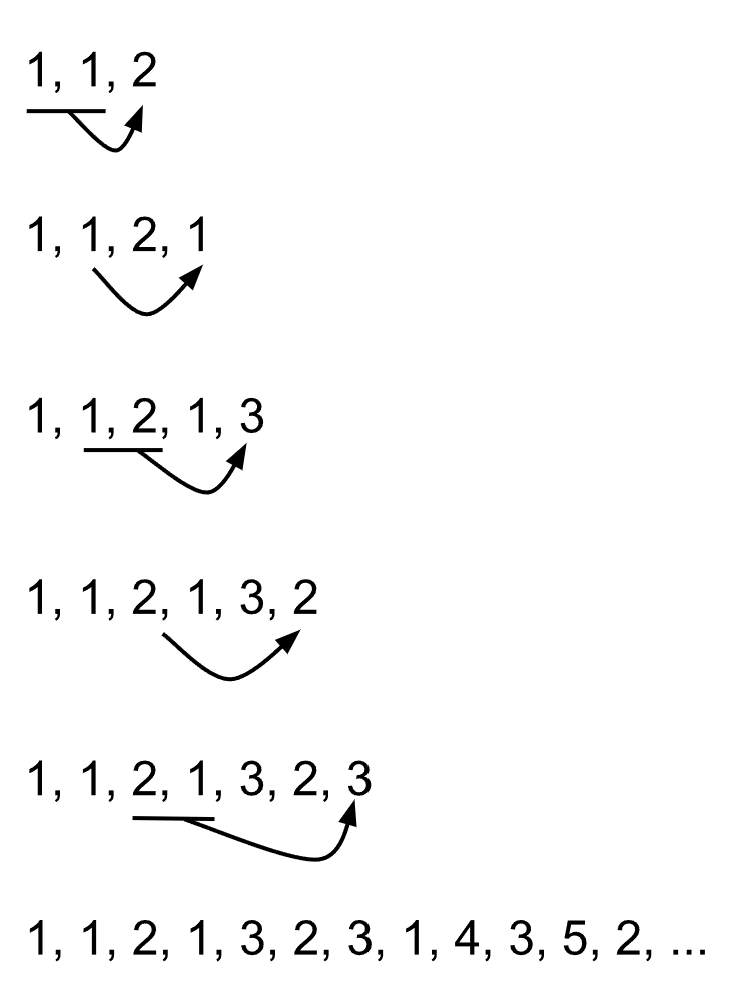

Now back to the first question. How can the rationals fit into the positive integers? For this, we look at a famous set of numbers: The Fibonacci Numbers. You may have encountered this sequence of numbers before. It starts with two numbers, 1 and 1. Then from those numbers onwards, each next number is the sum of the previous two numbers. So the third Fibonacci number is 1+1=2, the fourth 1+2=3, the fifth 2+3=5 and so on. 1,1,2,3,5,8,13,21, …. But now, let’s do something different. We start with 1 and 1 again, and add them to get 2. But now, the fourth term will be the right term in the addition of the previous terms. So since the terms to get 2 is 1+1, the right term is 1 and so it is the fourth term. The sequence alternates between adding and copying. And when you add to get the term, the addition is at a steady pace, moving a digit to the right for the next addition. For example, now we have 1,1,2,1. To get the next term, we add 1 and 2, because the previous addition was the left term and the term before it, 1 and 1. So the next term is 3. The term after that is copying the right term of the sum, so since the previous sum is 1+2, the next term after 3 is 2. It is a confusing sequence, but no worries, for I have a diagram to help illustrate it a bit better.

This is known as the Stern-Brocot Sequence. While tedious, it has a special property to it. If you were to add fraction signs between terms, you will get 1/1, ½, 2/1, ⅓, 3/2 and so on. The amazing thing is that in this sequence, every fraction appears once and only once, and it will be in its most simplified form. So you won’t, for example, see 2/4 or 3/6 because they are just ½, and ½ only appears once in the sequence. Because this sequence has this unique property of producing unique fractions, they can be put into a one-to-one correspondence with the positive integers. And so Cantor, with the help of Stern and Brocot, can put all the tourists in just one floor of infinite rooms. For both the positive and negative rationals, all cantor needs to do is alternate them like the integers, and they will fit snugly in.

Infinity is an abstract concept we came up with. It quantifies a value that can not be comprehended in our mind and gives meaning to a thing we can never visualise. While it does stretches our mind, it also shows us how limited our minds are, and how maybe there could be some other people out there in the universe that could explain it to us even better. Cantor helped us in our first step towards understanding infinity, and Maths is also constantly using it to help show results in the real world. The concept of infinity, while abstract within our mind, is an integral part in our real world. And as always, thanks for reading.